On February 27, 2026, Genentech filed a complaint at the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) alleging that Biocon’s importation of its pertuzumab biosimilar, BMAB 1500/PERT-IJS (“BMAB 1500”), violates 19 U.S.C. § 1337 (“Section 337”). Biocon’s Biologics License Application (“BLA”) for BMAB 1500 references Genentech’s PERJETA (pertuzumab), a HER2-directed monoclonal antibody therapy used in treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Genentech seeks a limited exclusion order through expiration of the latest Asserted Patent, cease-and-desist orders to block U.S. importation and related commercial activity, and a bond during the 60-day Presidential Review Period under 19 U.S.C. § 1337(j).

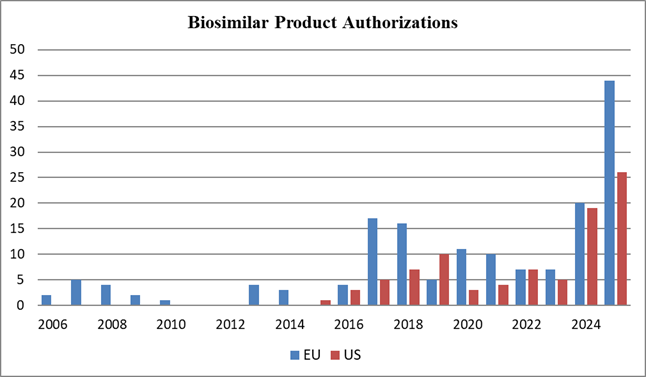

The Asserted Patents are: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,652,474 (the ’474 Patent); 11,597,776 (the ’776 Patent); 12,145,997 (the ’997 Patent); and 12,173,080 (the ’080 Patent). The latest expiration date of the Asserted Patents is September 28, 2031 (the ’474 Patent). The ’474 patent claims pharmaceutical compositions comprising a HER2 antibody and certain acidic variants thereof, and the related ’776 patent claims methods of making such compositions. The ’997 patent and the related ’080 patent claim methods for preventing reduction of disulfide bonds during an antibody manufacturing process. These four patents, along with 20 other patents, were asserted in one prior litigation under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in district court. That BPCIA litigation was filed by Genentech and Hoffmann-La Roche against Shanghai Henlius Biotech, Shanghai Henlius Biologics, Organon LLC and Organon & Co. (collectively “Henlius”) and involved another pertuzumab biosimilar. The 24 patents asserted in the BPCIA litigation covered various aspects of pertuzumab compositions, formulations, and manufacturing methods. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Henlius Biotech’s biosimilar (“Poherdy”) in November 2025, and the case settled in January 2026. The terms of the Henlius settlement agreement have not been disclosed.

Unlike district court litigations, Section 337 investigations are conducted by the ITC pursuant to Section 337 and the Administrative Procedure Act. They involve allegations that importation of specific goods infringes U.S. intellectual property rights. Proceedings include trial before an administrative law judge and subsequent Commission review. The proceedings are faster compared to district court litigations, typically reaching a final decision about 16 months after institution. The principal remedy is an exclusion order directing U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to stop infringing products at the border, although the Commission may also issue cease-and-desist orders. Unlike in district court litigation, the ITC cannot award monetary damages. However, companies can file parallel proceedings at the ITC and in district court.

Here, Genentech alleges that Biocon imported substantial quantities of BMAB 1500 from India before FDA approval, citing an October 18, 2025 shipment of more than 17,800 pieces of BMAB 1500. Genentech contends this conduct falls outside the patent infringement safe harbor under 35 USC 271(e)(1),[i] characterizing it as stockpiling of commercial supplies. Under this logic, Genetech asserts that Biocon’s acts constitute patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a)[ii] and 35 U.S.C. § 271 (g),[iii] Genentech challenges patents covering both the product (the ’474 Patent and the ’776 Patent) and its method of production (the ’997 Patent and the ’080 Patent), leveraging the ITC’s expedited timetable to potentially delay a new biosimilar launch in the U.S. market.

[i] Which only protect importation “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs or veterinary biological products.”

[ii] Direct infringement triggered by importing the patented invention into the U.S. during the term of the patent.

[iii] Direct infringement triggered by the importation into the U.S. of a product that is made by a process patented in the U.S.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this posting does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice or express any opinion to be relied upon legally, for investment purposes or otherwise. If you would like to obtain legal advice relating to the subject matter addressed in this posting, please consult with us or your attorney. The information in this post is also based upon publicly available information, presents opinions, and does not represent in any way whatsoever the opinions or official positions of the entities or individuals referenced herein.